Hungary Water: Part 2

March 21, 2022 • 3 Comments

This is the continuation of this  blog describing the recipe and my first try at recreating Hungary Water. I left the test batches to steep for about three months. I waited some months more to let the scents settle down and blend.

blog describing the recipe and my first try at recreating Hungary Water. I left the test batches to steep for about three months. I waited some months more to let the scents settle down and blend.

My first observation is that volume is important. By the time I strained the vegetable matter from my test batches, I didn’t get much yield—maybe half a cup per jar. The results were also very concentrated. When I do this again, I’m going to use at least a quart-sized container and more liquid.

The rosemary scent dominates the results, but that could be because it was the one element that was home grown and therefore freshest. All three bases initially overpowered the scent of the herbs but calmed down with time. The witch hazel version was fairly raunchy when it first brewed but is now the most pleasant of the three. It is a nice addition to a bath and as a facial astringent. I used the cider vinegar version (diluted) to rinse my hair after shampooing it. This is an excellent way to add scent and shine, but please be careful with color-treated hair as the vinegar can be drying. The vodka version was my least favorite. It killed some stubborn weeds in the driveway and probably any other living entity within five yards. I’m pretty sure the driveway glows after dark and the raccoons are building a bomb shelter.

My honest assessment is that a) a greater liquid volume would create a better balance of scents, b) the combination of herbs could possibly be simplified, and c) I need to do more research into a good liquid base for this purpose. The witch hazel is acceptable, but I’d like to keep exploring.

Bottom line: this experiment opened the door to some interesting possibilities for more research and experimentation.

Love, Hate, and Severed Heads – the Secret Life of Basil

February 20, 2022 • 2 Comments

Many herbs have stories, and basil has more than most. The name derives from the Greek basileus, which means kingly or royal. Associated with love potions, angry monsters, and tales of romantic tragedy (and decapitation), basil’s legend goes far beyond pesto.

Many herbs have stories, and basil has more than most. The name derives from the Greek basileus, which means kingly or royal. Associated with love potions, angry monsters, and tales of romantic tragedy (and decapitation), basil’s legend goes far beyond pesto.

Basil is associated with the masculine, Mars, fire, and Scorpio. It is a culinary herb and also a strewing herb, valued for its scent. As an inhalant, it stimulates the intellect. As an incense, it invokes the presence of astral and mythological creatures and gives strength to pursue positive expansion, releasing fear associated with spiritual growth. Traditional health uses vary. It is used in folk medicine to treat fevers, and there is some investigation being done on treatment for herpes-related conditions like shingles.

Basil is used cosmetically for brightening the complexion. Sweet basil oil (Ocimum basilicum) is used in perfumes and also in a scalp massage to stimulate healthy hair growth.

According to the Ancient World—or at least the Greco-Roman segment thereof—basil was associated with anger and insanity. Perhaps this comes from its association with scorpions, salamanders, and also the basilisk, a dragon-esque creature that could kill with a glare. Given all the cranky crawlies, it’s a good thing basil was reputed to draw the poison from venomous bites.

It’s hard to say when the humble herb moved from angry lizards to love potions, but by the Middle Ages a sprig of basil became a love token and a means of attracting wealth. It was also said to have grown at the site of Christ’s crucifixion—further evidence of its ability to repel evil—and in some regions was planted on graves. In India, holy basil (Tulsi) is used for purification and protection.

Basil’s twin spirits of love and hate twine together in Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron, a 14th Century collection of Italian tales. Many know the story from John Keats’s  1818 poem retelling the story. In a nutshell (or herb pot), lovely young Isabella is destined for an advantageous marriage but falls in love with a handsome servant named Lorenzo. Furious, her brothers murder the young man. Guided by the ghost of her dead lover, Isabella digs up his body, chops off his head, and buries it in a pot of basil. There, she can water it with her tears and waste away in fine tragic fashion.

1818 poem retelling the story. In a nutshell (or herb pot), lovely young Isabella is destined for an advantageous marriage but falls in love with a handsome servant named Lorenzo. Furious, her brothers murder the young man. Guided by the ghost of her dead lover, Isabella digs up his body, chops off his head, and buries it in a pot of basil. There, she can water it with her tears and waste away in fine tragic fashion.

For such a grim tale, it inspired a wealth of lovely pre-Raphaelite art, like this painting by William Holman Hunt.

Common garden basil is native to India and flowers in high summer. I’ve never found basil easy to grow indoors. It loves heat, but not too much; rich soil, but not too much richness; and exactly the right amount of water. A bright windowsill is good, but be careful not to introduce other plants nearby. I had a thriving pot of globe basil until I left a planter of cat grass beside it just long enough to deposit a swarm of pesto-loving aphids. The best home-grown basil I ever saw lived in a compost box beneath a tent of plastic that kept the cold dew off the leaves. There, the plants grew to a Jurassic size I’ve never been able to replicate.

Check this blog for my pesto recipe.

IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER: herbal medicines should be prepared and taken under the supervision of a trained professional (and that does not include me or this blog).

References:

I consulted quite a few sources for this blog, but here are the main ones:

Easley, Thomas, and Steven Horne. The Modern Herbal Dispensatory. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books, 2016.

Beyerl, Paul. The Master Book of Herbalism. Blaine, Washington: Phoenix Publishing Inc., 1984.

Grieve, Mrs. M. A Modern Herbal. London: Tiger Books International, 1992.

Cunningham, Scott. Cunningham’s Encyclopedia of Magical Herbs, 2nd edition. Woodbury, Minnesota Llewellyn Publications, 2020.

Rose, Jeanne The Aromatherapy Book: Applications & Inhalations Berkeley, California, 1992

Ten Days in a Mad-House

July 26, 2021 • No Comments

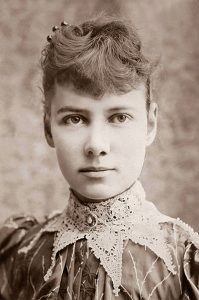

There aren’t many historical figures I want to fangirl over, but Nellie Bly (born Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman 1864 – 1922) makes the list. An American reporter, she pursued investigative stories at a time when women were doomed to penning fluff pieces. Bly soon tired of the society pages and insisted on challenging subjects. Danger was no deterrent – among other assignments, she covered the European Eastern Front during WWI.

There aren’t many historical figures I want to fangirl over, but Nellie Bly (born Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman 1864 – 1922) makes the list. An American reporter, she pursued investigative stories at a time when women were doomed to penning fluff pieces. Bly soon tired of the society pages and insisted on challenging subjects. Danger was no deterrent – among other assignments, she covered the European Eastern Front during WWI.

Around 2019, I read Ten Days in a Mad-House, Bly’s expose of the Women’s Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell’s Island. She got herself committed and posed as one of the female inmates to discover what went on inside. Needless to say, it wasn’t pretty. Her revelations of abusive living conditions and the casual cruelty of asylum officials shocked the New York public of 1887. Eventually, it led to reforms at the asylum. Her steady, detailed narrative stands up today as readable reporting.

I returned to Bly’s story in my research of Victorian-era asylums. When I learned there was a film adaptation, I quickly found it on Hoopla. Timothy Hines wrote and directed this 2015 production (10 Days in a Madhouse). Caroline Barry is charming as Nellie, but I question her chirpiness in places. And unfortunately, where the true story is dark enough, the movie gilds the lily in places. As a result, the tone comes out as spunky and sordid at the same time, making me wonder what audience they were aiming for.

That said, the movie worked well enough as a recap. The unsanitary conditions, bad food, inadequate heating, and casual cruelty are all part of the original. So is the maddening truth that institutions silenced the inconvenient far more often than they cured them.

Unruly women were deemed most inconvenient indeed.

DIY Historical Cosmetics: Queen of Hungary’s Water

April 26, 2021 • 3 Comments

Queen of Hungary’s Water aka Hungary Water has been one of my favourite scents for as long as I’ve been wearing perfume. It’s herbal rather than sweet, with a clean, bright finish. Though no two blends are exactly the same, lemon and rosemary are usually the dominant notes. As I was making this up, the scent of the herbs was almost dizzying. It’s like a herb garden in a jar.

Queen of Hungary’s Water aka Hungary Water has been one of my favourite scents for as long as I’ve been wearing perfume. It’s herbal rather than sweet, with a clean, bright finish. Though no two blends are exactly the same, lemon and rosemary are usually the dominant notes. As I was making this up, the scent of the herbs was almost dizzying. It’s like a herb garden in a jar.

Some sources claim Queen of Hungary’s Water is the first alcohol-based perfume, or at least the first European one, and dates from the beginning of the fourteenth century. It’s also used as a skin tonic, the herbal ingredients effective against acne and eczema, among other issues. In addition, it can be used to bathe the temples to cure a headache. It is for external use only. Do not drink it or take it as a tincture.

Ingredients are important

There are a lot of different recipes for Hungary Water, but be careful. Beware of recipes that use lemon verbena as a main ingredient as the essential oil of that plant has been linked to sun sensitivity, which can increase the likelihood of sunburn. Lemon balm does not have the same problem.

Try to get organic herbs and essential oils if you can. Good quality dried herbs will store in a cool, dry place until it’s time to make another batch.

Recipe:

Layer the herbs in a wide mouth jar. A mason jar is ideal (bigger is better – the herbs swell once the liquid goes in).

2 tablespoons of lemon balm

2 tablespoons of lavender

2 tablespoons of calendula

2 tablespoons of rose petals

2 tablespoons of chamomile

1.5 tablespoons of comfrey

1 tablespoon of sage

1 tablespoon of rosemary

1 tablespoon of peppermint

1 tablespoon of elderflowers

12 drops of helichrysum oil

Top with chopped lemon peel (1/3 of a lemon rind, pith removed)

Cover the herbs with apple cider vinegar, witch hazel, or vodka. Allow for a couple inches of liquid above the herbs. Store for several weeks, shaking a couple of times a day.

As this is my first time making this, I’ve done one each using the vinegar, witch hazel, and vodka to see which turns out best. Please see this blog for the results.

I based this recipe on several existing sources both in books and online, including this one, this one, and this one. I’ll adjust the ingredients as time goes on until I create my own preferred combination. For now, I’m sharing my experiment with you!

Post Script

Please note:

Yes, I am a writer of vampiric fiction, but before you get excited, dear reader, the Hungarian noble in question is not Elizabeth Bathory of “bathing in the blood of virgins” fame, nor does this post describe a bracing post-blood tonic or solution for that awful bathtub ring. I suggest a foaming cleanser with plenty of bleach for that.

Victorian Funeral Biscuits – the Recipe

• No Comments

Funeral biscuits played a part the Victorian tradition of death and mourning. I cover their history in my previous post on the topic, and now we come to the recipe.

Funeral biscuits played a part the Victorian tradition of death and mourning. I cover their history in my previous post on the topic, and now we come to the recipe.

Sadly, it’s hard to know exactly what the biscuits tasted like. Even if they were available in a museum somewhere, I’m not like the Eating History guys and willing to nosh on decades-old treats. To make things more difficult, I could not find funeral biscuits in a cookbook I trusted. One recipe included modern ingredients and others were vague to the point of uselessness. So, I set out to invent something from those items that appeared in the majority of texts.

Consistent ingredients were flour, sugar, and caraway seed. I tested various combinations of other things, including icing sugar, milk, and cornstarch. Results varied from interesting charcoal to hard as a brick. When I did finally achieve a good result, I understood why rationing during wartime finally finished off the production of these biscuits–they’re no good without lashings of butter.

Victorian Funeral Biscuits

Preheat oven to 350 F

Cream: 1.5 cups of sugar with 1 cup of soft butter

Add: 1 tsp vanilla and 2 extra-large beaten eggs (or 3 smaller ones). Mix until smooth

Sift: 2.5 cups of flour, 2 tsp of cardamon, and 1/2 tsp salt. Add to wet ingredients a bit at a time along with a tablespoon of whole caraway seeds (some recipes recommend toasting these before adding them to the dough).

Mix until all wet ingredients are absorbed. The dough will be slightly sticky. If you wish to use a cookie stamp, chill for a few hours before going further. Otherwise, make a small ball and press with a fork to form the cookie. Keep rinsing the fork in cold water to keep it from sticking in the dough.

Bake on a greased cookie sheet for 12 minutes or until the bottom just begins to turn brown. (Do not overbake!) Cool slightly before moving to a wire rack. The result should be a crisp, slightly caramelized bottom with a softer top.

As noted above, this recipe is only an estimation of what the original Victorian funeral biscuits might have been like. The quality of ingredients today is very different, as those of us who experienced “Buttergate” can attest. However, I think this is a reasonable approximation of the buttery, slightly spicy biscuit that’s perfect with tea after a brisk seaside stroll.

As noted above, this recipe is only an estimation of what the original Victorian funeral biscuits might have been like. The quality of ingredients today is very different, as those of us who experienced “Buttergate” can attest. However, I think this is a reasonable approximation of the buttery, slightly spicy biscuit that’s perfect with tea after a brisk seaside stroll.

Of Shortbread and Cannibalism

March 31, 2021 • 1 Comment

Imagine a knock at the door and, when you answer, the caller hands you a package. It contains a wrapped packet of biscuits tied with a black ribbon. Instantly, you know there’s been a death, and this is your invitation to the funeral.

Imagine a knock at the door and, when you answer, the caller hands you a package. It contains a wrapped packet of biscuits tied with a black ribbon. Instantly, you know there’s been a death, and this is your invitation to the funeral.

A Victorian Funeral Tradition

Funeral biscuits flourished as part of the elaborate panoply of the Victorian funeral. References to them are found in England and parts of North America. Surviving recipes are rare, which suggests they might have been very simple or an adaptation of something most cooks already knew how to make.

Those recipes or descriptions that do exist suggest a sweet similar to shortbread or a molasses cookie. More elegant households favored a lighter sponge  similar to ladyfingers or Savoy biscuits. The shortbread style often bore a design such as an hourglass, heart, cross, skull, cupid or other symbolic image. The use of such stamps gives us a clue to the consistency of the dough in use.

similar to ladyfingers or Savoy biscuits. The shortbread style often bore a design such as an hourglass, heart, cross, skull, cupid or other symbolic image. The use of such stamps gives us a clue to the consistency of the dough in use.

The biscuits appeared at the funeral as an accompaniment to a restorative glass of sherry or port wine. Mourners or to those unable to attend received wrapped packages of biscuits. And, as mentioned above, they could also be used as an invitation.

Bakeries produced biscuits to order, especially for large funerals. Between two and six biscuits were bundled in waxed paper. Sometimes, this wrapping bore a design with the usual skulls, hearts, etc. since the Victorians were apparently Goths at heart. At other times, the paper displayed the death notice of the deceased, a poem, or a Bible verse (see an example here). Black wax or a black ribbon sealed the package. For this keepsake of the departed, presentation mattered.

Digression alert: There is an odd parallel with wedding cakes here. If you’re royal, cake mementos can persist down the centuries. For those craving a slice of Queen Victoria’s wedding cake, this article is for you.

You Are Who You Eat

You Are Who You Eat

The funeral biscuit tradition faded with the advent of professional funeral parlors and the maelstrom of the World Wars, but its roots run deep in history. There is a connection between these tidy little biscuits and the the idea of claiming an energetic connection to the deceased.

Prior to the oh-so-hygienic funeral parlor, family members awaited burial in the home–in the parlor, if the house had such a room. Relatives, friends, and neighbors visited to pay their respects. According to folk tradition, objects belonging to or placed around the dead absorbed some of their qualities, and it was possible for the living to gain those qualities by possessing or consuming them. The same kind of sympathetic magic appears in Game of Thrones, when Daenerys consumes the heart of a stallion so that her child will have the horse’s strength. In both cases, a tangible (edible) medium transmits the deceased’s qualities to the living.

Neolithic funerals involved the occasional bit of cannibalism (several examples have been found in southern Iberia). In Central Europe during the Middle Ages, household bakers made “corpse cakes” (sometimes shaped like gingerbread men) from dough risen on the body. Mourners consumed the cakes to absorb the deceased’s virtues. In similar fashion, in Wales and the West Country of England, sin-eaters (usually someone at the bottom of the social scale) consumed bread and salt left on the body, thus absorbing the dead man’s guilt. In some accounts, villagers beat the sin-eater afterward to punish those transgressions.

There is a long and winding connection between corpse cakes and the Victorians’ polite shortbread marked with a skull. Nevertheless, given the nineteenth-century appetite for heavy symbolism, it’s likely at least some understood and accepted that grim association.

I did make an attempt at recreating funeral biscuits. Because this entry is already getting long, I will detail that adventure in another post.

Further Reading:

Frisby, Helen. Traditions of Death and Burial. Oxford, UK: Shire Publications, 2019.

Vervain: the Enchanter’s Plant

March 16, 2021 • 4 Comments

Forget using stinky old garlic against vampires. The Vampire Diaries ushered in a new era of preternatural pest control with vervain, making a plot device from a relatively common herb long associated with warding off unwanted magic.

Forget using stinky old garlic against vampires. The Vampire Diaries ushered in a new era of preternatural pest control with vervain, making a plot device from a relatively common herb long associated with warding off unwanted magic.

Curiosity prompted me to take a closer look at this plant, and what I found piqued my interest—especially since I feature herbalists in my upcoming books. Who doesn’t like a useful research rabbit hole?

Common names

Alternate names for vervain include enchanter’s plant, herb of the cross, and Juno’s tears. Some legends claim druids used it to purify their ritual waters. Others say Romans used bundles of vervain to cleanse their altars.

The Romans also called vervain herba sacra, or the “divine weed.” They believed it could cure the bites of all rabid animals, arrest the progress of venom, cure the plague, and avert sorcery. They even held verbenalia, a feast in the plant’s honor. Another name for vervain was herba veneris, so called because of the aphrodisiac qualities ascribed to it by the Ancients (presumably also the Romans).

Lore has it that vervain grew on the Mount of Calvary, where the faithful used it to staunch the wounds of the Saviour. For this reason, “Herb of Grace” is another popular name for vervain, although this term is also applied to rue.

This is the difficulty with studying herbs—proper plant identification is everything. Common names are confusing and using the wrong plant (especially in medications) could be hazardous.

Speaking of nomenclature, A Modern Herbal says the name vervain possibly comes from the Celtic languages, fer meaning “to drive away” and faen meaning “stone.” The name might reflect the herb’s early use in treating bladder ailments.

There are two kinds of vervain

Blue Vervain (Verbena hastata) is known as American vervain or false vervain and is native to North America. It has medicinal properties, but they are different from European vervain (Verbena officinalis), which is the kind I’m writing about here.

Verbena officinalis hails from the Mediterranean region and has escaped gardens to run wild in North America. This perennial likes roadsides and sunny pastures. It has white or lilac spiky flowers that bloom from June to October. Its stems are quadrangular and branch. The leaves grow in opposite pairs. It has little scent and a slightly bitter taste. When harvesting, pick the plant before it flowers and dry it immediately. Typically this happens in July, though this could vary with climate.

Don’t confuse these members of the verbena family with lemon verbena, an altogether different (and delightful) plant.

Uses of Vervain

Modern herbalists use Verbena officinalis as a stimulant, astringent, diuretic, nerve tonic, and fever medication. They employ it in the treatment of skin ailments and for depression following illness. It can be used as a tea to calm nerves and promote sleep or in a mouthwash against gum disease.

IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER: herbal medicines should be prepared and taken under the supervision of a trained professional (and that does not include me or this blog).

But back to the paranormal stuff.

Magically (or Magickally, depending on your preference) speaking, vervain assists purification, protection, blessings, and communication with nature spirits. Ruled by Venus, vervain belongs to the earth element. A crown of vervain worn by the magician will protect against evil spirits. It is used in ritual incense for exorcism and in prosperity spells.

References

I never met an herbal dictionary I didn’t like, so I have a lot of them—some from when I was a teenager, some barely out the Amazon carton. I consulted quite a few books to put this post together, so this is just a short list of the main sources.

Beyerl, Paul. The Master Book of Herbalism. Blaine, Washington: Phoenix Publishing Inc., 1984.

Easley, Thomas, and Steven Horne. The Modern Herbal Dispensatory. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books, 2016.

Evans, Ivor H. Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, 14th edition. Markham, Ontario: Fitzhenry and Whiteside Limited, 1989.

Grieve, Mrs. M. A Modern Herbal. London: Tiger Books International, 1992.

Lust, John. The Herb Book. New York: Bantam, 1974.

Rapping with the Dead

February 7, 2021 • No Comments

Who doesn’t love a good coincidence, especially when it involves ghosts?

Who doesn’t love a good coincidence, especially when it involves ghosts?

Recently I was blathering with a friend about contacting the dead (as one does while folding laundry). I’m stocking up on ideas for a new story, and it was an unplanned but fruitful topic. Literally minutes later, I got an email for a virtual event.

Cue Weird Homes Tour and Atlas Obscura featuring Brandon Hodge. Hodge owns an Austin, Texas residence stuffed with Spiritualism-related objects. For one very fun hour, Hodge took viewers through his collection of antique planchettes, Ouija boards, and other paraphernalia.

It was like a gift-wrapped package falling through the monitor and into my lap. Spiritualism fascinates me, and Hodge’s enthusiasm and fab website are an ideal introduction to the subject.

A Victorian Obsession

The Spiritualist movement gained traction in the mid-1800s. It gave us mediums, automatic writing, ectoplasm, spirit photography, and table-rapping.

Essentially, it’s summoning the dead for a chat. Believers included the rich and famous, from Lucy Maud Montgomery to Arthur Conan Doyle.

For a buttoned-up society focused on industry, cataloguing, and petticoats for the piano legs, it’s interesting how Victorians embraced the paranormal. Their enthusiasm can be seen by the many, many periodicals dedicated to the topic, such as The British Spiritual Telegraph.

Celebrity

Mediums achieved a kind of celebrity, like the Fox sisters in America. Some grew rich. Others were ingloriously debunked for coughing up gauze

“ectoplasm” or manipulating the seance props with wires.

The majority of mediums were women. This was one place she could take center stage without question. And, since the bereaved were willing to pay, she could also make a good living.

Spiritualism carried on—unsurprisingly—through the disasters of WWI and the Spanish flu epidemic until fading in the 1930s.

Stories

I’ve used the highlights of Spiritualism before. In A Study in Ashes, Evelina and Tobias attend a séance. At the time, I’d wanted to delve more deeply into the subject, but that wasn’t part of Evelina’s story. She simply paved the way for more.

Now—thanks to a chance lockdown presentation—I’m anxious to do more research. After all, what’s more perfect than something that is Victorian, paranormal, and involves intriguing devices? I’m positive there is a role for a planchette or two in my Hellion House series.

It’s all in the cards!

August 20, 2020 • No Comments

Would you like me to tell your fortune? For a silver coin, I will consult my tarot cards. Ah, yes, I foresee you’re about to encounter a large to-be-read pile…

Would you like me to tell your fortune? For a silver coin, I will consult my tarot cards. Ah, yes, I foresee you’re about to encounter a large to-be-read pile…

I imagined a unique set of tarot cards while planning the Hellion House series. The images in the deck came to me very strongly while I was first making notes about the books. Scorpion Dawn, Leopard Ascending, Chariot Moon—these are all airships, but those vessels got their names from the cards. Fortune’s Eve recounts the first time that tarot comes into play. For those who like to follow story breadcrumbs, pay attention to that scene.

Of course, it had to be a deck I’d never seen before, which meant recording the entire thing as it appeared in the story a bit at a time. Here’s what I know so far…

Suites

The deck has five suites (sky, fire, earth, water, spirit) of thirteen cards each. Each suite relates to an aspect of being. For instance, earth rules the material plane.

Images

Most of the images on the cards are single animals, plants, or other straightforward objects.

Readings

To cast a reading, lay out the cards in a triangle. They naturally fall into the rising, descending, or hidden positions on the three sides. Therefore, the leopard in an ascending position means that its influence is on the rise and all that fiery animal passion is going a-prowling. The closer it is to the apex of the triangle, the more pronounced its energy will be. If the leopard is on the other side of the triangle, it would indicate the hunt was waning or going awry. If the card was at the bottom of the triangle, it would mean kitty’s energy was turned inward, either asleep or rebuilding for a future time. A fulsome reading would involve a dozen or so cards.

Scorpion Dawn refers to the first awakening of the protective scorpion. The legend has it that when the mighty hunter Orion slaughtered far too many animals, the goddess sent the lowly scorpion to protect her creatures. Too small to be noticed, the scorpion nonetheless poisoned Orion with a sting to the heel. Never underestimate the little guy—or girl—especially if she gets this card.

The main function of the cards in the story is as a means of exploring the characters and their drives. Like all such elements in fiction, it’s a seasoning and not a main dish. Too much and it gets awkward, but it’s a useful way to highlight a moment here and there.

Custom illustration by Leah Friesen

Fish and Trips

July 3, 2020 • No Comments

Every so often I come across a reference to something that sends my brain scurrying down a rabbit hole. As a fantasy writer, I particularly love twists on everyday items that could otherwise slide into an ordinary social landscape. Food is a favorite, because we all encounter it on a daily basis and there are oh, so many possibilities.

Every so often I come across a reference to something that sends my brain scurrying down a rabbit hole. As a fantasy writer, I particularly love twists on everyday items that could otherwise slide into an ordinary social landscape. Food is a favorite, because we all encounter it on a daily basis and there are oh, so many possibilities.

Imagine yourself at a feast—maybe a good ol’ grimdark medieval banquet with dogs under the table chewing on Bob’s remains (what the guests haven’t already eaten). Or, perhaps you’re attending a prettier version of the above at the Sun King’s court, or even a Victorian soiree with champagne on ice and … someone serves a platter of fish, prized for its hallucinogenic properties. Chaos ensues.

Apparently, this is a thing. Several species of fish contain hallucinogenic toxins. The best known is Salema porgy (Sarpa salpa), a type of sea bream. Whether or not diners experience an effect from Salema may depend on the season or the diet of the fish—certain microalgae and also Posidonia oceanica, a kind of seagrass, is thought to contribute to toxins building up in the fish’s flesh (particularly the head). The delirious trip lasts for days.

Salema is found in the Mediterranean and East Atlantic, ranging from Great Britain down to South Africa. It is known in Arabic countries as “the fish that makes dreams.” Romans apparently organized entire banquets around getting stoned on Salema. I pity the slaves who had to clean up afterward but there is an excellent story scene there somewhere.

Sadly, although I have a good many historical cookbooks, I found no reference to preparing Salema porgy in Roman times. However, a search of the internet suggests grilled with salsa verde.

Thanks to Annie Spratt for sharing their work on Unsplash.

You Are Who You Eat

You Are Who You Eat

Who doesn’t love a good coincidence, especially when it involves ghosts?

Who doesn’t love a good coincidence, especially when it involves ghosts?